Seven Saints & Sages of Old and New

The fourth in our series of articles on “Why care for creation?“

Why should we be interested in saints and sages?

Saints and sages, because of their closeness to God and the deep wisdom they have absorbed, can provide us with useful insights into the workings of God and the world, and by word and example point is in the right direction of travel – one that leads to healing and oneness with all of God’s creation.

St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne (c 634 – 687)

Cuthbert became a monk in the tradition of the Celtic Church at the age of 17 and over time served in senior roles at Melrose Abbey and at the new monastery at Ripon. At a time when being a Christian was not the norm, monks devoted much time to being missionaries. Cuthbert travelled widely (on foot) meeting with and healing people, and preaching the gospel. He was well known for his austere holiness and devotion to God. One story about Cuthbert records that having prayed for hours standing in the sea, otters came and warmed his cold feet!

After several decades of this busy life, he felt called to a hermit lifestyle eventually establishing himself on the island of Inner Farne. Here Cuthbert was struck by the beauty of the eider ducks who also inhabited the island and made a decree that these ducks should be protected and that no one would be allowed to take the birds nor their eggs. This legend has led to Cuthbert being seen as the first conservationist.

However there might be a more interesting take on this story which concerns the interconnectedness that can exist between humans and wild creatures. To this day (but in decreasing numbers) there are islanders who each spring prepare homes for eider ducks with stone bases for the birds to build their nests with rooves overhead to shelter them from both weather and air borne predators. Once the nesting season has started these “duck farmers” keep watch over the eiders scaring away – foxes, eagles, gulls etc. Once the ducks have raised their brood, and left once more for the open seas, the farmers go to the nest and collect the down – the lightweight feathers – which the ducks pluck from their chests to line the nests. And this eider down then rewards the farmer with a good price.

Maybe Cuthbert, in banning the taking of the birds and their eggs, was actually fostering a system where ducks and humans could live together in harmony in a way that benefitted both parties. And surely that should be the aim of all relationships between humans and creatures – that they be based on understanding and mutual benefit.

St Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

Hildegard is well renowned as having successfully founded and run two monastic houses, written widely on the science of plants and their medical uses, on health and the science of the human body, as a composer of liturgical music, as a source of advice and teaching for many people – rich and poor – and for her theological insights which she gained for visions and about which she she reflected and wrote several volumes.

Hildegard’s deep insights and experiences of God reveal to her the interconnectedness and interdependence of all of creation. Hildegard’s gift of a way with words allowed her to articulate the very real presence she experienced of God being in and through and surrounding all of creation. She spoke of the Holy Spirit as Wisdom; as the Word quickening and enflaming and flowing through all that is created; and as Love as a matrix through which the world was created and by which it is sustained. She wrote how everyone contained “living sparks” of God’s love. Sparks we all receive but which we can also suppress. Hildegard understood the importance of repentance – for to live away from or in opposition to God leads to destruction. She wrote about “viriditas” – the greening power of the Divine that brings vitality and healing to all that has been created – bodies and souls alike. Interestingly it was Hildegard’s insight that it is not the soul that is contained within the body, but that it is the body that is contained within the soul.

Hildegard was clear that it is through being aware of, and working in harmony with, this divine life force, that salvation – the true fullness of life – is to be found.

For Hildegard it was obvious that the created – material – world can not be separated from the spiritual. Finding salvation, finding healing and wholeness in this life, can only happen when we recognise and live in parallel with the co-flourishing of the spiritual and the physical.

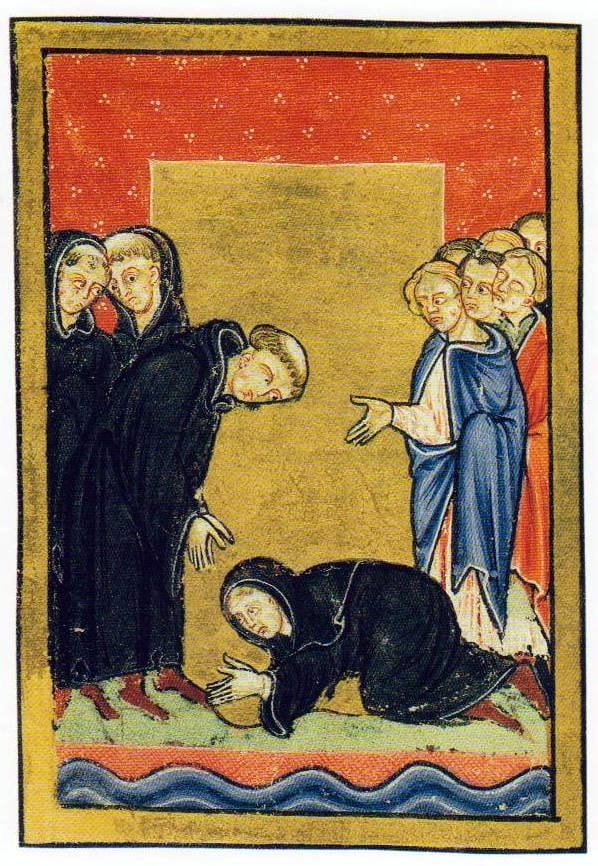

St Francis of Assisi (1181 – 1226)

St Francis’s reputation as a lover of birds and animals, goes before him! But we should be interested in him not just because he loved birds and animals, but because the way in which he did this which was in fact a whole life philosophy.

Where many young people may have sought riches and fame as a means of self identity – and self aggrandisement – Francis sought poverty and humility. By “betrothing” himself to Lady Poverty he adopted a lifestyle totally dependent on what God – through the bounty of creation – provided. He had no ties or commitments to family tradition, to social cliques, to business groups, or to fashion. He was not tied down by the need to look after property or ensure the growth of investments or keep hold of valuable items. He did not have to conform to the wiles of being a consumer. He didn’t have to conform to anything other than God’s love. So when he looked at birds and animals, or at the wind and the rain, or indeed at his fellow human beings, he saw only his brothers and sisters – i.e. those worthy of his love because they were all God’s children.

This, with our 21st century minds, we see as his realisation that all parts of creation are interconnected and interdependent because that is how God has made them. It is when we lose sight of or ignore that interconnection and interdependence that things go wrong – that rivers become polluted, that entire species become extinct, that the many are impoverished to satisfy the needs of a few. Francis still has much to teach us about the freedom that comes from embracing poverty.

St Kateri Tekakwitha (1656-1680)

Tekakwitha (her given name) was the daughter of a Mohawk father and a Algonquin mother (a Christian convert courtesy of a Jesuit mission). Diseases such as small pox, inter tribal wars and wars with the occupying French settlers, meant that Tekakwitha grew in a time of great turmoil and change. By the age of four she was an orphan and was then looked after by other family members. Her own bout of small pox may also have damaged her eyesight.

Later through her own encounters with Jesuit missionaries, Tekakwitha was drawn into her own growing faith in Jesus. The missionaries had carefully sought to find words and examples that would engage with the local cultures.

Tekakwitha vowed to remain a virgin declaring that she had dedicated her life to Christ. When she was later baptised, she took the name Kateri (after St Catherine of Sienna) but her conversion brought with it opposition from her local community and she was forced to flee. She joined a community at Sault Saint-Louis along with other indigenous peoples who had similarly converted to Christianity. She lived there until her early death, aged 24.

Tekakwitha, as with others of her generation, would have grown up with a well thought out native understanding that saw the natural world as sacred and its resources as treasures to be used with care and respect. Legend has it that as her faith grew so she spent many hours in the forests praying. She made crosses from sticks and hung them from trees to mark the stations of the cross. Other times she arranged stones on the ground as if they were a rosary.

Tekakwitha reminds us that through modernisation and industrialisation we can loose our connection with the wisdom that comes from being in close contact with the natural world – a wisdom and a world which come from God.

Katherine Hayhoe (Born 1972)

Katherine Hayhoe identifies herself as a “Climate Scientist who believes in God”. Her field is atmospheric science and she is a Master of Science and a Doctor of Philosophy. On top of this, she is an excellent communicator informing people about the reality of the climate crisis and how they can both shift their life styles and press for system change. However like the Old Testament prophets before, her message is not always accepted – and she has identified six stages of climate denial: “It’s not real. It’s not us. It’s not that bad. It’s too expensive to fix. Aha, here’s a great solution (that actually does nothing). And – oh no! Now it’s too late. You really should have warned us earlier.”

Nevertheless it is bringing together her faith and her scientific knowledge that empowers Katherine to seek a positive response that really is about bringing in the kingdom of God.

“Climate change is inherently unfair. Each year that goes by, it’s driving more people into poverty, depriving more of food, water, and a safe place to live, putting more at risk. This injustice resonates with all of us; and for me, it also speaks to the teachings of my Christian faith. Jesus told his disciples that they were to be recognised by their love for others: and what is climate change, other than a failure to love our sisters, and our brothers, and every other living thing that shares our planetary home?”

For Katherine her pressing message is what people – and especially Christians – should be doing in the face of the climate crisis. Saints and sages are not just people to admire: they are people to listen to and then follow through with action.

Vanessa Nakate (Born 1996)

In 2019, Vanessa began a solitary climate strike in Kampala, Uganda following the example of Greta Thunberg. From there she has gone on to become a world renowned climate activist.

Vanessa uses her passion for climate and justice to be prophetic about the climate crisis both through taking nonviolent direct action, setting up practical projects, and speaking truth to those in power – including addressing both the UN and the World Economic Forum – calling on the rich countries and their governments to support financially the most vulnerable and to urgently and drastically cut their emissions. In particular she highlights how the peoples of Africa have contributed least to the crisis, are underrepresented in international agreements, and yet are amongst those who suffer the most from the effects of the climate crisis.

Vanessa has set up various groups such as Youth for Future Africa and the Rise Up Movement to enable other young Africans to become successful climate activists that others cannot ignore. In her home country she has founded the Green Schools Project which installs solar panels on rural schools.

Yet Vamessa’s journey has not always been straightforward. In 2020 her face was cropped from a photo featuring Greta and other – white – activists. Her response to the news outlet that they “didn’t just erase a photo, you erased a continent” made headline news!

Vanessa draws on her faith to inform and sustain her activism. As she succinctly phrases it: “What does Jesus Christ have to do with the environment? Everything.”

Vanessa’s passion and commitment should encourage us to be as true to our faith in our commitment to stand up for climate justice.

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew (Born 1940) & Pope Francis (1936-2025)

Two spiritual leaders with world wide reach.

Bartholomew is the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and is well known both for his engagement with interdenominational and inter faith conversations, and for his concern for the environment: “For humankind and the planet as a whole, now is our kairos: the decisive time in our relationship with all of God’s creation, when we must respond in an opportune manner to protect life on earth from the worst consequences of human recklessness. May God grant us the wisdom to act promptly.”

In 1989 Bartholomew suggested that 1st September – the first day of the Orthodox Church’s year – should be a day of prayer for the protection of the natural environment. From this developed the Season of Creation Time stretching from 1st September to 4th October, the feast of St Francis.

Francis, as leader of the Roman Catholic Church, was equally passionate about building relationships. From the invitation to Bartholomew to attend his enthronement as Pope (the first time a Patriarch had done so since 1054) to their joint visit to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, from their shared support for Creation Time to their joint visit to the Moira refugee camp on Lesbos, both leaders have led by example to show the importance of that love that cares for and values everyone – every living being – as a brother or sister, as in integral part of the whole that is God’s creation.

Francis’s lasting legacy will be his encyclical Laudato Si – which takes its name from the Canticle of Creations which was St Francis’s own celebration of all creation as fellow siblings. Laudato Si provides a theological basis for recognising the value and interconnectedness of creation, and for caring for it with humility and urgency. It also calls on everyone to work together to mend the damage we humans have caused and to create instead a just and fair society. And it has given rise to the Laudato Si movement that empowers and activates Christians across the world in the challenge to “care for our common home.”

“Christians need an ecological conversion, whereby the effect of their encounter with Jesus Christ become evident in their relationship with the world around them. Living our vocation to be protectors of God’s handiwork is essential to a life of virtue; it is not an option or secondary aspect of out Christian experience.” (LS, 217)

Both these saints urge us to actively embrace sibling love, to ground our relationships in the understanding that all creation is interconnected and that all of it is to be valued and treated with care as God-given. It is to be hoped that all church leaders will follow their examples in calling on everyone to repent and reorientate their lives in response to the call to care for our common home.